From busy indigenous communities to a hard-scrabble pioneer town to a manufacturing and learning center in east central Wisconsin, so much history has accumulated on the shores of the Fox River and Lake Winnebago. Let’s imagine together a series of moments—many small, some large—taking place at specific locations to see how history stacks up upon this land.

Six moments at six locations from the past 150 years reflect on UW Oshkosh’s expanding mission of serving the people of our region and state:

1868

Date: Tuesday evening, May 12

Location: Oshkosh City Council Rooms, southeast corner of Main and Otter streets

City offices at the corner of Main and Otter, Oshkosh Public Museum photo

In the municipal government offices, downtown, we can imagine city clerk J.B. Powers, and other staff counting ballots from the day’s citywide referendum. The question: Should Oshkosh tax its residents in order to build the state’s third normal school, a place where young men and women would be trained for teaching positions in schools throughout the region?

State regents already had selected the city as its choice for the school two years earlier. This came after city boosters mounted a successful bid for the honor, competing against communities such as Neenah-Menasha, Omro and Fond du Lac.

City Clerk Josiah Powers, Oshkosh Public Museum photo

The choice of Oshkosh for the normal school made great sense to the regents. Blessed with waterways and growing railroad connections, Oshkosh was the state’s third largest city and a central hub of commerce and transportation in the Fifth Congressional District.

Still, years later, bickering among city leaders on the exact placement of the school led the state legislature to force a decision and require that the people of Oshkosh have a final say.

City leaders and local newspapers made the case of the economic stimulus ($30,000 annually!) and cultural impact the school would bring to the community. Opponents to the plan, however, focused on the expense of building and maintaining a normal school and opined that Oshkosh needed important infrastructure improvements on which tax monies would be better spent.

Oshkosh Normal School building, circa 1871

In the end, on that spring evening in 1868, Powers counted the votes from the five city wards and discovered in the final tally of 1,043 to 498 a clear mandate, confirming both the leaders’ and the citizens’ commitment to supporting an institution of higher education in the city. Few universities were built from such democratic origin. While the campus and community have grown, the commitment the city makes to the University has never wavered nor has it been taken for granted.

1916

Date: Wednesday morning, March 22

Location: Original Normal Building, Algoma Boulevard

Professor Harry Fling

They pulled the blankets taut and cried out for him to jump. Flames and smoke at his back, science instructor Harry Fling realized there was no other way to escape. Forced to give up his attempts to save books from the second floor library, he leapt from the window of the burning Normal Building. Recuperating from a dislocated shoulder at the local hospital, Fling surely fretted over the fate of his school, job and students.

Fortunately, Fling’s injuries were not severe. But the Oshkosh Normal School was nearly destroyed by the fire.

Specialized campus structures like the auditorium, gymnasium and Industrial Building (later, Harrington Hall) survived, but most of the classrooms, laboratories, studios, library, museum, offices, the elementary and middle school that the Normal operated and most of the equipment were lost. Could the school survive such devastation?

Ruins of the original Oshkosh Normal School building

School President John Keith worked quickly, traveling throughout the city to talk to clergymen about the possibility of the Normal operating temporary classrooms in churches. With their assistance, students at the Oshkosh Normal School missed only one day of class.

On the day after the fire, Board of Regents President Duncan McGregor toured the damage and—from the chancel of the First Presbyterian Church—promised the assembled students and staff that a new building would be authorized with haste. Much to the satisfaction of Fling, his colleagues and students as well as the City of Oshkosh, teacher education would survive the devastating fire.

1920

Date: Wednesday morning, March 17

Location: C&NW Railroad station, Division Street

They came from all over the Fox Cities, some from as far away as Wrightstown. Two train cars drafted into service brought 84 visitors—all enrolled in an education course offered through the Normal School’s new Extension Department—to campus in order to observe firsthand the work of the training school. The school’s children along with Normal students guided the visitors around, and faculty gave special demonstrations of classroom techniques. The domestic science department served them all a lunch of scalloped potatoes, cocoa and coffee.

Prior to 1919, Oshkosh Normal taught all of its classes on site in Oshkosh. Most classes required students to commute to campus at least several times a week, always during daytime hours. For people working full-time, particularly degree-seeking teachers, this proved burdensome and costly. To provide out-of-town students with access to higher education, it was clear that Oshkosh Normal had to take a page from the University of Wisconsin and deliver learning opportunities beyond traditional campus boundaries.

In-person extension courses in American history and sociology were initiated in Appleton and Kaukauna respectively during the fall semester 1919. Extension students met weekly on Saturdays to hear the lectures of Oshkosh faculty members. The next semester featured that education course which particularly attracted Catholic nuns in northeastern Wisconsin.

It took several more decades for Extension classes to fully develop at Oshkosh but, in time, Oshkosh instructors were teaching in communities as distant as Coloma, 60 miles to the west of campus. This commitment to expanding access was more realized when WSU Fond du Lac opened in 1968 as a full branch of the Oshkosh campus. Today the University’s online courses, in-person cooperative programs and two access campuses in the Fox Cities and Fond du Lac provide many different ways for regional students to more conveniently take courses from UW Oshkosh.

1952

Date: Thursday, January 21

Location: Dempsey Hall, Algoma Boulevard

In what might have been the briefest of any of the school’s commencement exercises, Donald Corrigall ’52 and MBA ‘76, of Oshkosh, received a rolled diploma from Ray Ramsden’s office in Dempsey Hall. Corrigall’s smart suit and pocket square convey something of the moment’s significance. He is being awarded the first undergraduate degree in liberal arts from the newly renamed Oshkosh State College.

Looking on, President Forrest Polk, who had dedicated his whole career to teacher training, might have harbored a few misgivings, fearing an expansion of the liberal arts curriculum might detract from the institution’s original mission—teacher preparation. For Ramsden and other College administrators present, including Roger Guiles, whose 1949 doctoral dissertation was used by the Board of Regents to help convince the state legislature and governor to permit the expansion, however, the moment portended a bright future. Polk soon retired, Guiles assumed his position, and Oshkosh State College began expanding in relevance to the families and students of Wisconsin.

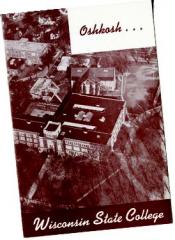

Early brochure for the newly renamed Oshkosh State College

In its first catalog for the new program, Oshkosh State College argued that its goal in liberal education was to develop the “free person,” someone who pursued a full, satisfying and worthy life, as well as the “citizen…who recognized their duties to others.” To accomplish this worthy task, the College began to develop departments in the humanities as well as the social and natural sciences. In time, with the liberal arts firmly established, further expansion to the College’s curriculum ensued. Professional degree programs in business (1963) and nursing (1966) were eventually added, thus creating the basis of a true, regional University. Despite President Polk’s fears, teacher education at Oshkosh would remain a core mission and erode neither in quality nor reputation. In fact, it would expand in its own right, to the benefit of schools and school children statewide.

1968

Date: Wednesday night, November 20

Location: Newman Center, corner of Elmwood and Irving

Campus Newman Center

The African American students who assembled that night at the Newman Center, the campus Catholic center, were angry. Over the past several months they had been harassed, cheated out of their financial aid, disrespected and lied to. University administrators were moving slowly on redressing their concerns, and the students felt ignored. For those present at their meeting, that night was about plotting a strategy for pushing their demands for equitable treatment forward.

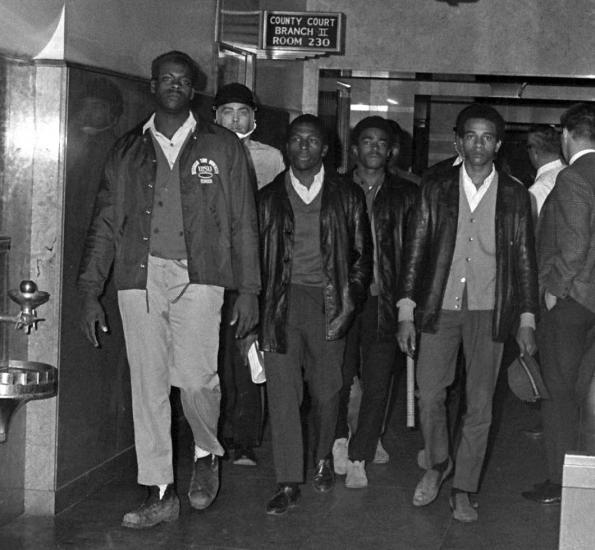

Students taking part in the Black Thursday protest in front of President Guiles’ office suite

There were no sizable numbers of black students at Wisconsin State University-Oshkosh (Oshkosh State College’s successor) until 1965, when an active recruitment process began to bring African Americans students from Milwaukee, Racine and other communities to campus. By fall 1968, the new and expanded class of African American freshmen, many of whom were veterans of escalating Civil Rights protests throughout the state, were determined to demand—and no longer wait for—change.

The students weighed their options. Some wanted to let the University’s process play out while others made radical suggestions that frightened the moderates of the group.

The students argued and debated and, ultimately, agreed to go as a group to President Guiles’s Dempsey Hall office the next morning and force an immediate response to their demands.

Arrested protestors in the Winnebago County Court House

Uncertainty and fear haunted the students that night. What if their confrontation of the president got out of hand? How would white faculty, staff and students respond to their actions? What would their parents say? The Black Thursday protest the next day resulted in the expulsion and arrest of 94 black students. While they were later invited to return to campus, most did not or could not. Some went to other universities, others to new careers. One was sent to Vietnam. The lives of all the Oshkosh 94 would change dramatically as a result of the collective decision made that night.

1996

Date: Saturday, March 16

Location: Kolf Sports Center, High Street

An unguarded Shelly Dietz prepares to shoot

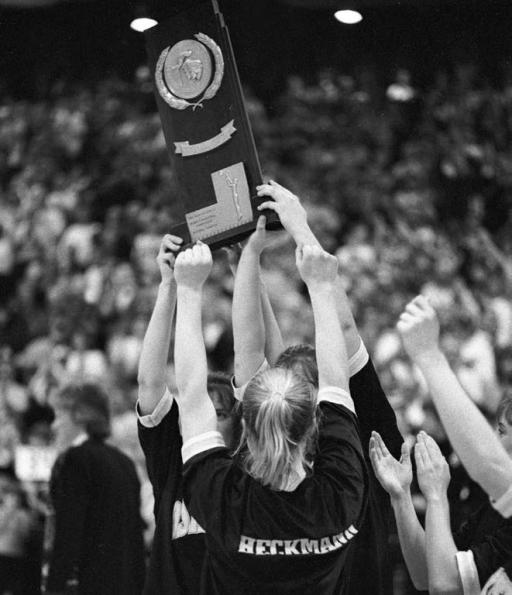

First the buzzer, then screams, hugs, pandemonium and the sound of Celebration by Kool and the Gang. The UW Oshkosh women’s basketball team just won the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division III national title!

In 1996, the Oshkosh women were dominant, beating teams throughout the season by an average of almost 28 points. The bitter memory of a near-miss shot at the championship the previous season inspired them mightily throughout the tournament.

A perfect season, that’s what a NCAA Division III record crowd of 4,001 packed Kolf Sports Center to see and celebrate that night. The Titans’ triumph would not come easily. Coach Kathi Bennett, a member of Wisconsin basketball royalty, had patiently developed the team over several years in pursuit of her first national title. Only one game against the formidable Mount Union Purple Raiders that had made equal short work of their bracket, stood between Bennett and her first championship. The Purple Raiders’ strategy was to put two or three defenders on Titan star Wendy Wangerin ’98, and thus shut down the inside game. The Titans responded by moving the ball around the perimeter, where guards Sarah (Heckmann) Ferge ’98 (15 points) and Shelley Dietz ’97 (with six three pointers) were ready with deadly accuracy.

Oshkosh players raise their championship trophy at the conclusion of their game against Mount Union

Coach Kathi Bennett

Not since the 1923 football season had an Oshkosh sports team enjoyed a perfect season. And none have since. Women’s basketball at Oshkosh began as early as 1897 and predated men’s play, but in time that tradition was lost. It was only truly revived after Title IX was passed in 1972. Less than 20 years later, the women were a common presence in tournaments. And by that night in March 1996 they were poised to reach the pinnacle of their sport and celebrate with the entire UW Oshkosh campus and community their hard-earned glory.

Read more about UWO’s history: uwosh.edu/150/