by Stephen Kercher

Professor of History

As the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh celebrates Women’s History Month during our sesquicentennial year in 2021, it seems the perfect time to reflect on the impact women have had on our campus community.

Students in my History 411 Research Seminar this semester are contributing to the effort by interpreting and narrating some of the many untold histories from our past. As I guide their research I am often drawn to stories of the dedicated faculty who have taught here—particularly the stories of women, such as Katherine Alvord and Aleida Pieters, whose names are not attached to campus buildings and whose influence on students far exceeded their brief stays in Oshkosh.

I think, too, of women born in other countries who came to this institution and contributed—and continue to contribute—mightily to the diversity of faculty ranks while injecting a much-needed dose of international perspective and cosmopolitanism to our neck of the woods. Take, for instance, the impact made here by the long-forgotten foreign language instructor Alice de Barcza, quite possibly the most interesting woman to ever teach at UW Oshkosh.

A bright beginning

Born Alicia Liphardt in Warsaw, Poland in 1910, the daughter of a wealthy polonized German father and Italian mother, she received the kind of rich educational experience enjoyed by members of her class and was fluent in three languages by the age of five.

She studied art in Berlin during the waning years of the Weimar Republic and then married Jerzy Romaszkan, a brilliant man who possessed wide-ranging artistic and architectural skills, a knack for translating the poet Rainer Maria Rilke and, not least, a baronial estate in the beautifully hilly Hutsul region of the eastern Carpathians.

It was here that Litka (as Alicia was called by friends) and Jerzy entertained some of the most renowned figures of the Polish literary, art and music scene—before they were forced to flee from the invading Nazis in 1940. Not long after entering Hungary and spending time in a refugee camp, Jerzy died from tuberculosis.

Displaying a tenacity and resourcefulness that would thereafter mark her remarkable life, Litka served as an interpreter for the Red Cross, designed silk ties for a textile firm and through the Polish underground met and soon married Kari (Charles) de Barcza, a Hungarian count who as vice president of the Federation of Hungarian Factory Industries in Budapest was doing his best to secretly frustrate the Nazi’s attempt to consolidate control over Eastern Europe.

As acting Charge d’Affaires for sovereign Catholic Order of Malta, de Barcza’s claim to diplomatic immunity helped spring him from a concentration camp near Vienna. In December 1944 he joined Litka and several of his family members and relatives at the de Barcza countryside ancestral manor in the hopes that they would safely wait out the end of the war there.

Best-selling author

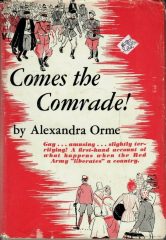

What happened to the couple over the next year after the invasion of Soviet military forces and the traumatic reconstruction of postwar Hungary and Poland became the subject of two international bestsellers, Comes the Comrade! (1950) and By the Water of the Danube (1951), written under Litka’s pen name (in order to protect relatives behind the Iron Curtain) Alexandra Orme.

What happened to the couple over the next year after the invasion of Soviet military forces and the traumatic reconstruction of postwar Hungary and Poland became the subject of two international bestsellers, Comes the Comrade! (1950) and By the Water of the Danube (1951), written under Litka’s pen name (in order to protect relatives behind the Iron Curtain) Alexandra Orme.

The manuscript of the former, written in 1946 while Litka was simultaneously earning income designing patterns at a fabrics plant and illustrating children’s books, was stuffed in a cookbook and thereby eluded MVD (Soviet secret police) detection when the de Barcas fled to Switzerland later that year on a milk truck. It detailed how Soviet troops raped and pillaged their way across the Hungarian countryside but ultimately met their match in Litka. Through guile, determination, a hastily acquired ability to speak Russian and keen insight into the minds of the boorish infantrymen, Litka was able to save herself and her husband’s relatives (though not their country estate) from harm.

The latter book continued the story of Litka’s survival in Budapest and a risky visit back to her beloved Warsaw, what many critics considered to be the best writing of her young career.

A subsequent stint as a receptionist, interpreter and fashion designer for Paris luxury house Marcel Rochas would inspire de Barcza’s third book, Paris Original (1954), a work of fiction that mixed the story of a Polish expatriate love triangle with gimlet-eyed satiric observation of Parisian haute couture. She would not have been able to experiment with fiction and extend her writing career had it not been for the success of Comes the Comrade!

Initially published in England and distributed throughout the British Empire with the title From Christmas to Easter (1949)—and bearing the clever subtitle “A Guide to a Russian Occupation”—sales and critics’ reviews proved very encouraging.

Still, money was tight for the de Barczas, even though by 1949 they were living affordably in Positano, Italy. Litka, apparently the couple’s sole breadwinner, was set to begin a job as cook for a London hotel—among her many talents, she was reportedly a great cook and her bigos (a traditional Polish stew) in particular the “food for Olympians.” But news of the book’s selection as a money-in-the-bank Book-of-the-Month Club selection, talk of serialization in Reader’s Digest and the procurement of American visas sent the de Barczas happily to New York City instead.

The road to Wisconsin

Before long the couple moved to Washington, D.C., and Litka began teaching Polish, German and French to Air Force and Navy personnel at the Lacaze Academy of Languages. A 1955 speaking tour in support of her three published books brought her to the North Shore Club in Menasha and an opportunity to reconnect with a childhood friend from Warsaw now living in Oshkosh, the talented artist Felicia Krance.

In a Madison beauty salon a short time later, de Barcza learned that Oshkosh State College was looking to hire someone to replace its one retiring French instructor. A successful interview with college president Forrest Polk brought an offer to teach both French and German. “We are attempting to restore some of the values which the teaching of languages holds,” Polk wrote to her in June 1955, “by offering this coming year both beginning German and continuing with French.”

Considering the fact that German had not been taught to post-secondary students in Oshkosh since 1919, Polk was justified to express some “hope (that) we may expect a real revival in the language field.” “You don’t know how happy I am to spend a school year/or maybe my whole life in Oshkosh,” she wrote back, “where I found so many good friends.” Fortunately for de Barcza (and her husband), her eligibility to teach was not disrupted by the old Normal system rule that prevented married women from teaching on the Oshkosh campus.

As she prepared for the move to Oshkosh, she wrote Polk and requested that her teaching schedule “be made compact so that I might have as much time as possible to devote to my writing.” Her intentions were to finish work on a second novel titled Natalie (1957), a story about a 14-year-old Polish teenager coming of age while struggling to survive in war-torn Budapest.

As she prepared for the move to Oshkosh, she wrote Polk and requested that her teaching schedule “be made compact so that I might have as much time as possible to devote to my writing.” Her intentions were to finish work on a second novel titled Natalie (1957), a story about a 14-year-old Polish teenager coming of age while struggling to survive in war-torn Budapest.

She had long maintained an interest in Hutsul folk culture, nurtured through a longtime friendship and correspondence with the Polish writer Stanisław Vincenz, and hoped to illustrate a book of Hutsul fairy tales for American readers. But these plans never materialized because of difficulties she encountered with publishers.

Oshkosh State students and faculty attending her December 1960 talk on “writing and the problems of having works published” at Reeve Memorial Union undoubtedly learned the details of these difficulties. But the record also indicates that de Barcza was a dedicated language instructor and played an active role in advising the campus French and German clubs.

Even for a woman who had previously been able to draw from great reservoirs of energy and demonstrated admirable multitasking abilities, de Barcza’s attention to teaching (in the fall 1962 semester she had 114 students in her German classes) and her well-known commitment to helping students “with various language problems” might have placed limits on her artistic ambitions.

Return to Poland

She retired from teaching in June 1971. She longed for her native Poland and had visited there after her husband’s passing in 1963. It is possible that a basement flood in her Oshkosh home in the spring of 1973—destroying a rich archive of manuscripts, drawings and correspondence with Polish artists and intellectuals—might have further prompted her decision to return to Warsaw.

As de Barcza’s friend, the Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist Mary McGrory later informed newspaper readers throughout the United States, de Barcza returned “home amid the intense emotions and exhilarating danger that are oxygen to Poles, to enjoy the theater, the music, the conversation that flourished despite the grim, gray government.” She collapsed on a Warsaw street in September 1973 and died shortly thereafter.

UW Oshkosh legacy

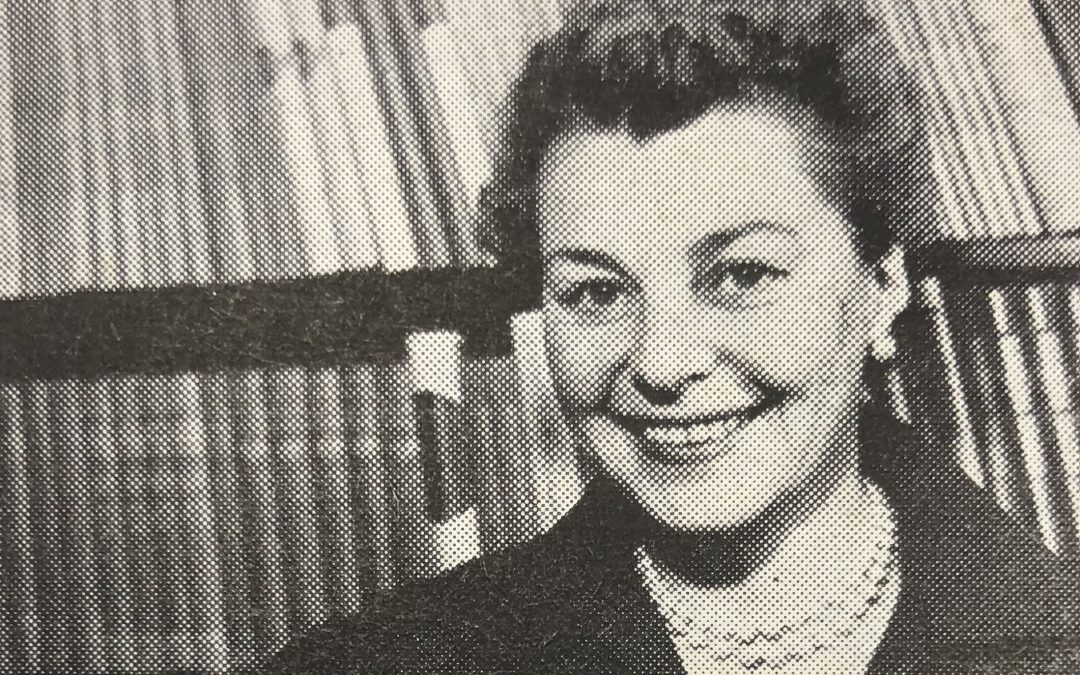

“She was ridiculously accomplished,” McGrory remembered. “She could write, draw, paint, sew and cook.” A “beautiful woman, with huge blue eyes, an elegantly blunt nose and the figure of a whippet,” she was recalled by one alumnus as a “splendid presence in Dempsey Hall.”

German students at UWO paid homage to de Barcza in 1975 by performing a satiric German-language play Kriemhilds Rache (which she adapted from the 1924 Fritz Lang film) in the basement of the Newman Center.

Today’s global languages and cultures department prepares UWO students for the global workforce.

Colleagues in the foreign language department (which grew from one to 17 faculty members over the course of de Barcza’s teaching career in Oshkosh) prized the “continental dimension” she brought. But for students in my research seminar to understand the full range of de Barcza’s contributions to the University, we need to hear from former students and colleagues.

In the meantime, I invite you to visit the University Archives on the third floor of Polk Library and page through the books that de Barcza donated in 1956. There too you may leaf through old volumes of the campus yearbook, The Quiver.

Archives has created a website devoted to UWO history, and here you will be able to access Campus Stories oral histories, link to a broad range of online exhibits and make use of a free searchable archive of our very good student newspaper Advance, dating from as far back as 1894. In all of these sources you will find stories of other fascinating women who have taught here and contributed much to our institutional strength over the past 150 years.

If you have stories or memories of Alice de Barcza or other faculty members to share with those of us researching the campus history, please contact Stephen Kercher at kercher@uwosh.edu.

Throughout 2021, UW Oshkosh is celebrating 150 years of excellence and opportunity as we mark our sesquicentennial celebration. Since our inception in 1871 as the Oshkosh Normal School for teacher training, our dedication to quality and innovative higher education has been a hallmark of our success as a premier comprehensive institution. Over the decades, our name has changed several times and our educational focus has expanded to meet the needs of students in our region and beyond. Learn more at uwosh.edu/150.